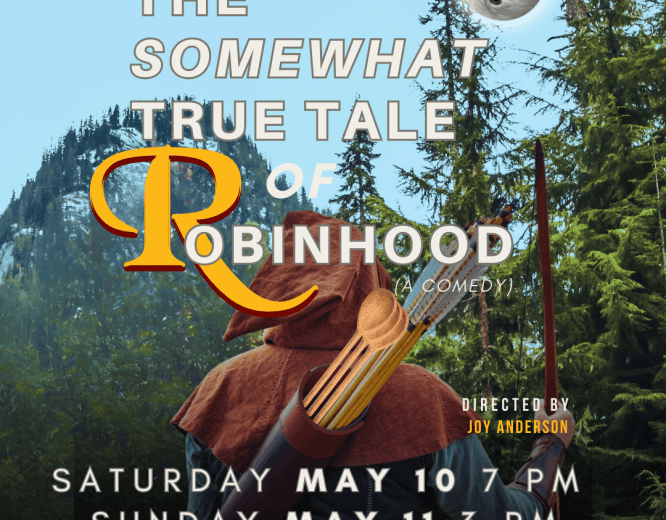

At the Foot of the Tree: Reflections from Pittsburgh

Note: Hannah Cranston ’09 Godwin shared this reflection from Pittsburgh, where she is a Youth Care Worker at Holy Family Institute’s Journey of Hope Program. She went to Pittsburgh to work with refugee resettlement efforts through Compass AmeriCorps. Regarding the experience of living near the Tree of Life Synagogue and the aftermath of the Oct. 27 shooting there, she wrote “I am filled with gratitude for the way EMHS has shaped the way I meet joyful and tragic events in my life, and especially grateful for the songs that… have been written on my heart.” Photos by Hannah Godwin.

At the Foot of the Tree

Every stone, flower, candle, and piece of paper alive in this growing memorial is a separate story. Here are my three.

I went to the synagogue with a slip of paper in my hand, an illustration torn from a children’s book about gnomes: the common sparrow. On the 31st, I’d dislodged a burnt sparrow from the out-take pipe of the dryer in a closet in Nazareth, one of the houses I work. I’d cradled it down the stairs and out the door, remembering our dead, and thinking, “Not a sparrow falls…”

This slip of paper I placed at the foot of Dr. Jerry Rabinowitz’s white wooden cross. Dr. Rabinowitz is beloved in our community, a caring professional who did what he could to heal the sick while honoring the dignity of each patient. He had been training his replacement, getting ready to rest easy in retirement with his family. I’ve heard the tremor in the voices of those who remember him and felt their controlled anguish as they seek the words that will tell again how kind, how manifestly decent, how bright. I secured my sparrow with three small stones and unfolded a rain sodden child’s drawing beside it. Small offerings.

The sunny chrysanthemums in the orange bucket are the weight a stranger placed in my arms as I stood before the crosses shaking in my too-thin sweater, hiding my face in my scarf to weep. I have no memory of what this person looked like and it’s possible I never saw them. I’d been holding myself and making a concentrated effort not to sway. My legs proved unreliable. The mums anchored me, rooting my feet to the spot. I held on tight, opened my eyes, emerged from behind my scarf. My shirt is still stained green from their fresh cut stems. I wanted to keep them, or at least to keep one. Now I was able to form a thought, attempt prayer.

The sunny chrysanthemums in the orange bucket are the weight a stranger placed in my arms as I stood before the crosses shaking in my too-thin sweater, hiding my face in my scarf to weep. I have no memory of what this person looked like and it’s possible I never saw them. I’d been holding myself and making a concentrated effort not to sway. My legs proved unreliable. The mums anchored me, rooting my feet to the spot. I held on tight, opened my eyes, emerged from behind my scarf. My shirt is still stained green from their fresh cut stems. I wanted to keep them, or at least to keep one. Now I was able to form a thought, attempt prayer.

I mentally stumbled through Psalms 23 and 139, then looked up for a place to put the flowers. I arranged them in an orange bucket full of rain water, crushed the leaves I’d stripped in my palm, and took in the myriad petals of the hundred bouquets heaped about me. I wanted to gather them all up and dump them into the buckets to halt their wilting, but I stepped back again to watch as mothers and fathers trundled their children along the caution tape line.

“Yes, it is sad. Uh-huh. Look. Yeah, they are sad too. Me? Yes, dear, I’m sad.”

It’s not the first time I’ve soaked up the comfort that parents extend their children. And the tyke in a superman suit and cape, the huge-eyed, curly-haired princess, the infant on his mother’s hip, a young woman who had walked here in flip-flops with no socks on her feet, the knee-high brothers, the schoolgirls in their grey-blue sweaters and skirts. This hopeful parade caused more than one mourner to share a cautious smile. Then the leather-jacketed man who bore eleven sunflowers, one to place beneath each cross, then stood beside me to pray in a whisper. I remembered Simon Wiesenthal’s The Sunflower: The Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness. In this Holocaust memoir, the sunflower is both a link between heaven and earth and a symbol of the atrocities of war. Wiesenthal, a prisoner bound to brute labor in a Lvov work squad, resents the tall sunflowers that mark the resting place of the Nazi dead. His own people are piled up and forgotten in mass graves.

The turquoise mason jar was riding along in my car, rolling on the floor on the passenger side until I returned to retrieve it. This is why. A grey-haired Jewish woman came to stand at my side, offering three tea candles and a book of matches.

“Would you like to say a prayer? It is okay if you are not Jewish. You may pray in English.”

“How should I pray?” I ask. She showed me Psalm 23 on her phone.

“That is what I have been praying,” I tell her. “Do you know…the one about being hemmed in? Being knit together in our mothers’ wombs?”

“Yes,” she replies. There is also this,” she says and shows me her phone. I read, “I lift my eyes to the hills. Where does my help come from? My help comes from the Lord. Maker of Heaven and Earth.”

Sounds of EMHS choir…

And with the next verses, a sound came to me clearly: Eastern Mennonite High School choir, singing a song from Felix Mendelssohn’s oratorio, Elijah, in four parts, “He watching over Israel, slumbers not nor sleeps/ He slumbers not/ He slumbers not/ He slumbers not/ He slumbers not/ Sleeps not/ He watching over Israel slumbers not nor sleeps.”

Each successive phrase swells and breaks gently as the first recedes. Not one is sung alone. My prayer wove up through many remembered voices. I knelt before the hilled heap of flowers, placed my three candles in a triangle, and struck a match. A damp wind snuffed it out immediately.

In the next moment, a bearded, bespectacled man was kneeling at my side, saying with grave humor, “We will do this.” He labored to light those candles. No sooner had we a little flame going than the wind put it to rest. Again and again the small flame sputtered out, and my new friend’s determination was unchecked. We built little walls around our candles with the stones. We sheltered them with our hands, endeavoring not to scorch each other.

In the next moment, a bearded, bespectacled man was kneeling at my side, saying with grave humor, “We will do this.” He labored to light those candles. No sooner had we a little flame going than the wind put it to rest. Again and again the small flame sputtered out, and my new friend’s determination was unchecked. We built little walls around our candles with the stones. We sheltered them with our hands, endeavoring not to scorch each other.

“I’m okay with fire.” I tried to tell him. “I don’t want to hurt you.” Finally I scrambled to my feet. “I have to get something from my car. I’ll be right back.” I didn’t know what I would find, but the mason jar was exactly right. I hurried back. We slid the weak brightness into the jar. It dropped perfectly and was out. Another reverent stranger approached and announced that he’d retrieve a longer lighter. And then, at last, the prayer and the candle were nestled, burning, into the whole.

I can’t tell you how long I stood there. I do know that many people came and went but that there were a handful who, like me, could not force their feet away from that ground. I thought about taking off my shoes. I thought about overturning every rain-filled candle, relighting each, and watching the collected blaze. Finally, I knew I had to go. It was All Soul’s Day. I was hungry, exhausted, and I needed to get myself to work. I searched the mourners’ faces for a person who might accept an offered matchbox and chose a young Jewish man with two small sons huddled against his black suit. I pressed the box into his hand, crossed the street and looked back to see the three already on their knees.

I can’t tell you how long I stood there. I do know that many people came and went but that there were a handful who, like me, could not force their feet away from that ground. I thought about taking off my shoes. I thought about overturning every rain-filled candle, relighting each, and watching the collected blaze. Finally, I knew I had to go. It was All Soul’s Day. I was hungry, exhausted, and I needed to get myself to work. I searched the mourners’ faces for a person who might accept an offered matchbox and chose a young Jewish man with two small sons huddled against his black suit. I pressed the box into his hand, crossed the street and looked back to see the three already on their knees.

As I write this a little over a week since the massacre, I have just finished reading Mendelssohn’s song and found in it the promise I forgot as I stood with the mourners at Tree of Life: “Shouldst thou walking in grief languish, he will quicken thee.” Though these words are sometimes impossible to speak, I will always be able to sing them.